King Lear

By William Shakespeare, directed by Michael Hurst

Circa Theatre, Wellington, until June 18.

Regarded as one of the greatest in the canon of Shakespearean plays, King Lear, currently playing at Circa Theatre, is a monumental work of epic proportions, operatic almost, and in fact is two stories rolled into one; that of Lear, King of England who misjudges the loyalties of his two daughters and suffers inextricably for this and The Duke of Gloucester who like Lear, is made an outcast by the actions of his sons.

It literally canvasses ever aspect of the human condition and emotion such as love, loyalty, betrayal, forgiveness, morality, religion and even the whole meaning of life and contains numerous scenes of violence, murder and mayhem.

And while the setting is all in England, in this production, set during World War II, the many scenes move from indoors to outdoors, with cliff tops during raging storms a major part of the play’s climax, adding further challenges to a successful production of the play.

Yet for the most part, Circa’s production, directed by Michael Hurst, does achieve this and everything comes together with consummate ease in a simple, but innovatively staged version, designed by Andrew Foster, that nevertheless doesn’t distil any of the passion or emotion from the play, portraying in graphic detail the harrowing experiences that Lear, a man “more sinned against than sinning” has to endure.

The actors use the large open space of the set, unencumbered by an array of furniture and props, to great effect, the opening court scene particularly effective in this regard, giving a wonderful sense of the epicness of the piece, while focusing on the lyricism of the dialogue.

Mention must also be made of how modern technology is creatively used for the storm scene.

But it is the actors that bring any play alive and everyone onstage in this production equips themselves with the necessities for giving strong stellar performances. At times though, the passion and emotion of some performances takes over and the clarity of the dialogue is lost.

In the lead roles are two greats of New Zealand theatre – Ray Henwood as Lear and Ken Blackburn as Gloucester. As Lear, Henwood has all the authoritarian mana of a patriarch expecting to do well by his daughters, but when one doesn’t comply with his wishes and the others turn against him, he begins to question his own mortality and thinks he is going mad, Henwood’s transition through these stages is masterly, as he becomes almost child-like in the end.

And as Gloucester, Blackburn portrays his self-effacing nature well, unaware of being duped by his bastard son Edmund until it is too late. And Edmund is given a great interpretation by Guy Langford, his opening soliloquy proclaiming that he follows the laws of nature, leaving in no doubt the type of character he is. And as the Fool, Gavin Rutherford gives a delightful performance in trying to assist Lear by commenting on his actions with humorous quips and jibes and lots of physical antics.

All of this makes this Shakespearean tragedy one well worth seeing.

Circa’s King Lear is a stupendous production. We enter into an atmospheric place with subdued lighting and haze. Andrew Foster’s vast set rears up in front of us in expectation of this vast play: King Lear is one of ‘the biggies’ of the canon.

Two huge perpendicular walls, set at an angle to are us, are drab green and distressed. One has a large ballroom-like window and one door, the other a large picture of the King’s visage which dominates us like an Orwellian big brother. On either side of the picture are three distressed hanging working lights that are bulbs surrounded by the upended wire frames of bedside lamps.

The walls have an almost wet sheen as though they drip and the floor is of second hand wood. There’s an earthiness here. The walls size feel claustrophobic and sit like two sides of the Dover Cliffs. Opposite, at the end of the other wall by the door, are written the letters “NIHIL”.

We are in a meeting place with chairs and a table preset. It’s like a church hall taken over by the army and neglected. The wide open playing area affords little room to hide.

The cast gather for the well-known first scene in which King Lear expresses his “darker purpose” of divesting his kingdom into the hands of the next generation so that Cornwall and Albany may avoid hostilities. The actors are beautifully costumed by Gillie Coxill in 1940s garb. The men in suits and uniform look smart, attractive and all business; the supporting actors are ‘women of the workforce’ and men in suits and later military uniforms, and Lear’s daughters resplendent in the dress of the day.

Goneril (Carmel McGlone) is all silk and smiles with red hair; Regan (Claire Waldron) is the wide-eyed blonde with a simple, yet elegant, dress and fur; Cordelia (Neenah Dekkers-Reihana), the dutiful daughter, is in uniform with a simple black bob. I’m put in mind of the then Princess Elizabeth as the uniformed mechanic of WW2. Immediately these ladies are defined for us. In a room full of men they are separate not only for their position but their gender. In Shakespeare’s day such active, powerful women were a rarity and here, in 1940, began the rise of women in the workplace so these costumes are a beacon of colour on a drab stage.

The programme comes with a synopsis of the play, which I feel is a little disappointing – surely you trust your production to tell a story – but simply put this is a play about fathers who put their faith in the wrong places. Lear’s story of betrayal by his two eldest daughters is paralleled by Gloucester’s betrayal by his youngest son. We are introduced, as is Kent, to Edmund and then Lear introduces us to his daughters and we are away.

The company – and with the large range of age and experience it does feel like a company in older sense – are uniformly strong. They understand the language and are at ease with telling us their stories. Each character is well rounded, confidently portrayed, making each part of the whole their own.

Michael Hurst’s casting also reinforces the many parallels between these stories, I’ve already commented on the differences between the daughters. So too Edgar (Andrew Patterson) and Gloucester (Ken Blackburn) share black hair while Edmund (Guy Langford) clearly sticks out as the blonde bastard. This is used obversely with Kent (Stephen Papps), the loyal servant to Lear, being matched physically to Oswald (Nick Dunbar). Both tall and lean as whippets, they could be brothers from another mother.

We are able to follow the action clearly even though the differing places are not generally made explicit. There are also some judicious edits that keep the story propelling forward (I must admit I’ve never really been a fan of Cordelia’s interjections in scene one). Hurst allows the words to do their work, though sometimes these are hard to make out, and there are some chunks of paraphrasing. The unforgiving hard surfaces of the set means that anything spoken at volume and speed, unless it is brilliantly articulated, is lost to us. And sometimes accents and the soundscape have the same effect: Kent’s regional accent sometimes gets in the way and Gloucester’s words in the tent with the storm outside are inaudible.

I am centre and in the third row. Talking with others at interval and after I find I am not the only one straining to hear. Poor Tom’s speech in the storm is unintelligible unfortunately, one punter quipping “well he’s mad so it doesn’t matter,” with another punter chiming in with “if Shakespeare wanted unintelligible gibberish he would have written unintelligible gibberish.” Fair point.

Certainly the second half fares better, either because the actors have worked it out or because there is less sound to compete with. Some judicious level-setting from the designer and operator would be worth the work. This is not to say that Jason Smith’s sound design is obtrusive in any way; there is always that shake down on opening night when, suddenly, the audience’s clothes soak up voices, but with the experience onstage I’d expect better. Smith supports and creates atmosphere brilliantly, effective both because of its quality and prudent use.

Ray Henwood in the titular role plays Lear as a man with some self-knowledge of his own decline. He clasps his heart and asks not to be mad as if these maladies were already on his mind and that this has forced his abdication. His is a measured Lear in a simple but elegant suit with a cane, a nod to his age.

His railing against his daughters flies out of him with petulance and with virulence. His daughters’ reactions are all within their own characters and yet each time he explodes he is full of spite and malice. As Goneril says, “As you are old and reverend, should be wise” – with his age should come wisdom. This is followed by some of the most unkind things said to a daughter. While Goneril and Regan are certainly after their own advancement, you can see they will not take these vicious tantrums and you agree with them.

This measured-ness does mean that after the storm it seems he’s more happy, having let go, rather than actually mad. Henwood’s at his best here: playful and light. However during the storm all the dialogue is spoken as if within a room rather than outside, weakening the storm’s effect. His is a simple death, effecting yes, but with words like “Howl” and, during the last scene, his reticence to emotion makes him feel still walled off rather than having embraced himself fully.

Gavin Rutherford’s Fool is played as an intellectual simpleton; his off the wall dialogue comes from the realm of madness itself. It is quite affecting in that here is a madness that is not self-induced but with it comes some clarity. He is heart breaking in the storm when trying to give cover to Lear.

However I really don’t understand the Fool becoming a soldier for the ‘enemy’. His facial birthmark clearly seen through the balaclava, he is the soldier who will hang Cordelia and then be slain by Lear. It destroys the emotional work he has done before.

As I’ve said the company is uniformly strong but this production is owned by the villains. While Neenah Dekkers-Reihana’s Cordelia is a delight in its simplicity, which, as the lynchpin of honour, makes her final entrance in Lear’s arms such an emotional climax, both McGlone and Waldron relish their sexy climb to power, and Langford is extraordinary.

McGlone’s heated ice-queen dominates the stage, her husband, and the comedy with a wink and a dagger. I would not like to come up against her machinations. Like Thelma and Louise, she’d rather kill herself than let that fall to anyone else.

Waldron, as Regan, is astounding. Perfectly the middle daughter, she starts like Princess Anne with an almost ‘horsey’ voice and develops into a joyous unfettered sadist to rival Bond’s Xenia Onatopp. Her thrill during the eye gouging scene is a piece of perfectly pitched acting: so bold an offer that might easily topple but her commitment and presence makes it squeamishly believable.

Guy Langford has it all. The villain is always given some of the best lines and Langford delivers on every one of them. From comedy to falsehood, to strength, to the devil he delivers his words trippingly on the tongue with shade and light and such relish.

Hurst’s direction is spectacular. The story is clear, the characters well developed, each carrying a clear backstory. He has created a wonderful production that brings all creatives onto the same page and delivers with gusto. The musty, bleak world is balanced by some very fine comedy – I think a revelation for some in the audience. The choreography keeps the relationships between the characters fresh and alive, our eye moving and roving or being brought to a particular point for emphasis. With the designers he creates the many and various locations with ease.

I’m not a fan of the storm which consists of a fantastic, if low volume, soundscape and the actors wandering in and out of a square patch of rain/static. Is this a throwback to the Big Brother image at the beginning? In a set of perpendicular lines this act of nature is strikingly square as well.

That quibble aside, I adore the whole of the play. It is done with energy, understanding and is compelling. Clearly this is an important event in the Wellington theatrical calendar and I hope it is supported as it should be. I will definitely be going back for a further viewing, if only to stand up for bastards.

King Lear at Circa

Review by Howard DavisIn order to celebrate it’s 40th birthday, it is perhaps fitting that Circa Theatre should pick a production of ‘King Lear,’ since it’s also somewhat fortuitously Shakespeare’s 400th anniversary. If some of the more cerebral poetry is lost in Michael Hurst’s streamlined, full throttle production, it’s more than made up for by plenty of lascivious violence designed to entertain the groundlings.

Scholars believe ‘King Lear’ was probably written around 1605, between ‘Measure For Measure’ and ‘Macbeth.’ Like ‘Macbeth’ and ‘Cymbeline,’ it has a specifically British rather than English or European setting, for explicitly political reasons. Two years earlier Elizabeth I and her court had retired to the royal palace at Richmond, where the Chamberlain’s Men (presumably with Shakespeare among them) performed before her for the last time in early February. Soon afterwards, Elizabeth caught a chill, slipped into a dreamy, melancholy illness, and died, sixty-five and childless. It is therefore hardly surprising that Shakespeare’s contemporaries would appreciate the significance of a play that deals directly with issues of inheritance and royal succession, especially as his new patron James I desperately wanted to unify the spasmodically warring kingdoms of England and Scotland into a peaceful union.

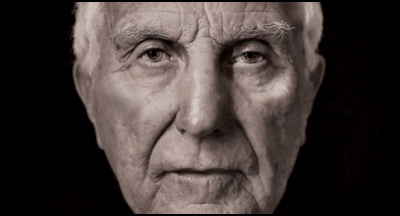

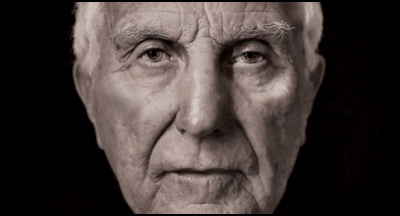

Ray Henwood as King Lear

Although Shakespeare lifted much of the story from Holinshed’s ‘Chronicles,’ Lear is also mentioned in Spencer’s ‘Faerie Queene’ and had already been dramatized a few years earlier as ‘The True Chronicle of King Leir and his Three Daughters.’ Shakespeare’s version first appeared in quarto as ‘The History of King Lear’ in 1608, while the folio version entitled ‘The Tragedy of King Lear’ is a 1623 revision. For many years, editors tended to conflate the texts, but current scholarly practice is to analyze them to separately. Astonishingly, Nahum Tate’s hugely popular version of ‘King Lear,’ which was performed regularly from 1681 to 1843, gave the play a happy ending.

Fortunately, perhaps, that is no longer the case. The Circa production explores the play’s twinned themes of sight and insight, pride and ignorance, blindness and madness, chaos and darkness with a uniformly somber palette, which makes the shedding of blood (when it comes, as we know it must) all the more shocking. For this tragic drama is also a heightened melodrama – a family romance in which the extremities of civil war (treachery and torture, sex and murder, betrayal and forgiveness) are all portrayed in extremis. Director Hurst (who himself played the Fool in a recent Auckland production) comments – “as we unpacked the action in rehearsals, we kept opening enormous caverns of significance, where the play seems to reach beyond its verbal confines.”

Which is, of course, precisely the reason why Shakespeare’s tragedies remain so relevant and timely even today. The violence deployed by Macbeth as he desperately clings to power has been duplicated in the actions and behavior of any number of petty dictators, not least in Russia. Hamlet’s dithering equivocations have plagued many a troubled, love-struck adolescent bent on self-destruction and revenge. And all the elements of the OJ Simpson story were already present in ‘Othello,’ three centuries earlier. Shakespeare’s great quartet of tragedies depict moral dilemmas whose contemporary consequences are plastered over today’s headlines on a daily basis.

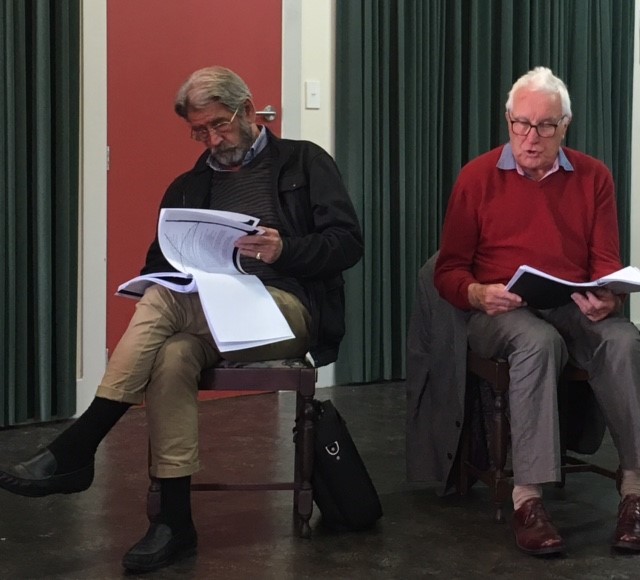

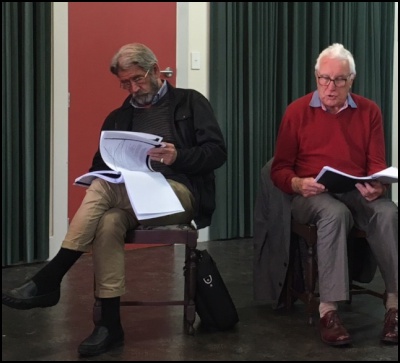

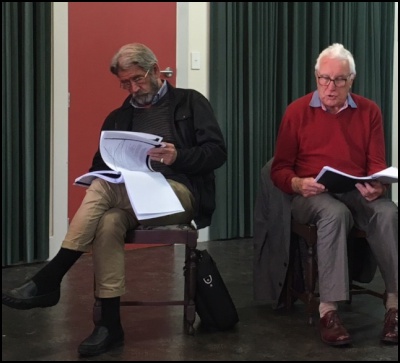

As we watch the lugubrious and somewhat abbreviated action unfold with pre-ordained precision, we also become aware that we’re witnessing a theatrical torch being passed from grizzled veterans such as Ray Henwood (Lear) and Ken Blackburn (Gloucester) to a younger generation.

Ray Henwood (Lear) and Ken Blackburn (Gloucester) in rehearsal – over 100 years of acting experience!Carmel McGlone as Goneril and Claire Waldron as Regan are suitably maleficent, while Guy Langford and Andrew Patterson are magnificently matched as the rivalrous siblings Edmund and Edgar. The set and lighting design by Andrew Foster and the mid-C20th costumes by Gillie Coxhill are subtly shaded in subdued hues of grey, brown, olive-green, and khaki. Jason Smith’s minatory sound design effectively complement the production, without overwhelming it. If Gavin Rutherford’s Fool seems slightly too autistic, it doesn’t detract from a genuine ensemble production in which the significance of the sub-plots are elevated so that their doubling of the main themes are clearly reiterated: “nothing comes from nothing” and “men must endure their going hence even as their coming hither – ripeness is all.”

Circa Theatre presents:

William Shakespeare’s KING LEAR

Shakespeare got his “King Lear” story from an early chronicler, Holinshed, (who had in turn got it from an earlier source). As well as this there had been an anonymous stage adaptation of the story “doing the rounds” and performed in London about ten years before Shakespeare’s play appeared. Both of these told the story of the semi-legendary Leir of Britain and his three daughters Gonorilla/Gonerill, Regan/Ragan and Cordeilla/Cordella. In both Holinshed’s version and the anonymous play, there is a happy ending, with the aged king reinstated on the British throne by his daughter Cordelia’s arrival with her husband the King of France’s troops to defeat the armies of the traitorous dukes of Albany and Cornwall..

Shakespeare’s dramatization, with its bleaker denouement to the story held the stage until the Puritans closed down all the theatres in 1642. With the Restoration theatres were reopened, but a new generation of playgoers found the uncompromising tragedy of the Bard’s Lear too much to stomach – this encouraged the Poet Laureate of the age Nahum Tate to rewrite the play along the ”happy ending” lines of the earlier versions. It wasn’t until over a century later that the great actor Edmund Kean reinstated Shakespeare’s tragic end to the drama – and even then the battle for fidelity’s sake continued to be fought well into the first half of the twentieth century over heavily cut scripts, and reducing or taking out supporting roles by various managers, directors or actors themselves, wanting to emphasize the role of the eponymous leading character….

Today, people responsible for productions pride themselves upon up-to-the-minute historical research and textual fidelity, even if there’s an equally compulsive desire on the part of directors to update the context of the play’s action, ostensibly for purposes of better connecting with modern audiences. It seems that British comedian Michael Flanders’ throwaway line during the course of his and Donald Swann’s revue “At the Drop of a Hat” concerning a dissertation on Tudor England theatrical performance – “Anything to stop it being done straight!” has become true of most present-day performances of theatrical and operatic classics.

Stage traditionalists must feel as though they get a hard time of it these days, but they can take heart from the pleasure and satisfaction to be had when encountering updated productions whose creators and organizers know what they’re about. So it was on Saturday night at Circa Theatre with director Michael Hurst’s production of Lear, which seemed to me to be securely grounded in its own “time”, the ambience suggesting the Second World War era, and the context one of military conflict. Once the frisson of encountering the update’s impact at the play’s very beginning – a shadowy, almost “film noir” scenario featuring people furtively smoking and soldiers with guns checking the environs in a “put that light out” kind of way – had been “squared up to”, and the King and his court been introduced to us in their gloriously-arrayed mixture of 1940s military and civilian clothes, we settled down to listening “past” our visual realignments and into the heart of the business, contained of course in the language and its interchanges.

Lear’s court resembled a smartly-run consortium’s board-room, one involving both military and civilian personnel. And there, in the commanding personage of Ray Henwood was the king himself, autocratic and imperious, walking with a stick, and wielding it with complete authority. His daughters and their respective entourages awaited the King’s pleasure, Goneril and Regan, the two eldest, seeming to anticipate the demand that they declare absolute and unequivocal love to their father. The elder sisters spoke in reply first, Carmel McGlone’s Goneril honeyed of voice, beautifully modulated and completely without spontaneity, and Claire Waldron’s Regan fulsomely sing-song but mechanical, and sounding increasingly like clockwork as she proceeded – both declaring their actual feelings and intentions as clearly to all excepting their father as if they had spoken their thoughts out loud.

A marked contrast came with Lear’s questioning of his youngest daughter, Cordelia, portrayed with youthful wholeheartedness by Neenah Dekkers-Reihana, her sincerity palpable and vulnerable in manner, but steady and unswerving in effect, engendering shock among allies and antagonists alike – the King’s anger was perfectly in context with his disappointment at Cordelia’s “Nothing” answer and his “Nothing will come of nothing” warning reply. The reaction to all of this of Lear’s uniformed right-hand man, the Duke of Kent (played by Stephen Papps) I found a bit puffy and blustery of manner at first, but once his defence of Cordelia in front of Lear had earned him his banishment, and occasioned his return in disguise to continue serving his master, I thought his portrayal as a loyal retainer deeply moving, rich in truth and honesty.

Articulating his “Stand up for bastards” speech while having his way on an office desktop with some acquiescent “temp” girl, was something of a virtuosic theatrical feat on the part of Guy Langford, playing the role of Edmund, illegitimate son of the Earl of Gloucester, a loyal friend of Lear’s. Very much the “young rake on the make” Edmund racily and almost engagingly outlined for us his scheme to undermine his half-brother’s legitimacy in his father’s eyes, and wheedle his way into favour with either (or both) Goneril and Regan. He made the most of his “heavenly portents” speech before convincing his brother Edgar that the latter had incurred their father’s displeasure, and that he (Edgar) had better go and hide out until further notice. I liked how Edgar (played by Andrew Paterson) convincingly presented a more rough-hewn, less “courtier’d” manner than his half-brother, credible in his despair at his father’s anger, and his bewilderment regarding what he might do to right the alleged wrong.

Edgar’s course, to take refuge in the countryside as a beggar, brought him into direct contact with the estranged Lear and his Fool (the latter a virtuoso portrayal by Gavin Rutherford of one of literature’s most powerful archetypes, the wise jester – more of him below….) at the height of a storm. In some of the most visceral language ever accorded the elements by any storyteller or poet, the words became stinging, biting, oak-cleaving cataracts and hurricanes. All of this was superbly and variedly detailed by Henwood, his character’s troubled place in the cosmos transfixed at that moment by a squared volume of rain-spattered light mid-stage, drawing our focus into the square and similarly flailing our own sensibilities – a most telling piece of interpretation and production. Having been then directed by the solicitous Kent to a hovel, Lear encountered Edgar, disguised as “Poor Tom”. Andrew Paterson’s portrayal forcibly put across the character’s deranged quality with heightened volume and dramatic gesture. Though much of his diatribe couldn’t be deciphered, his piteous sotto-voce asides kept the character’s purpose clear for us amid all the bluster.

So to Gavin Rutherford’s Fool, somebody appearing to be a “Billy-Bunter in an airman’s cap” Fool, but obviously a force to be reckoned with, a presence off whom Lear’s own words bounced and faltered, as when the king responded to the banter about making something from nothing with a hollow-sounding and throat-catching “Nothing can be made out of…….” And how tellingly was the Fool’s “old before thy time” jibe underscored with just enough music of derangement as to indicate Lear’s unnerving by his own fears, with “Keep me in temper! – I would not be mad!” Throughout, the characterizations of each of the actors made me more aware than ever of how both the Fool and Kent each try to protect and safeguard their lord and master, Kent from his enemies without and the Fool from Lear’s own foibles within.

As for Ken Blackburn’s playing of Gloucester, the portrayal graciously and naturally conveyed the character’s one-dimensional amiability right at the outset, along with a comprehensive lack of insight into either of his sons’ true mettle. This obtuseness led to his downfall at the hands of ruthless ambition – and only in the wake of his savage blinding by both Regan and her husband Cornwall in revenge for his continued support of the king, did the first glimmerings of truth begin to shine for him from within. The blood-drenched beginning of this process brought us into direct contact with Peter Hambleton’s single-minded depiction of Cornwall’s ugly thrust towards power, and, even more disturbingly, Regan’s naked blood-lust, Claire Waldron here most viscerally and repellently conveying her delight at Gloucester’s disfigurement. Less overtly but as slyly evil was Nick Dunbar’s beautifully-crafted Oswald, ostensibly a tool of his mistress Goneril’s machinations, his impulses at her beck and call, his manner as pragmatic as any soldier of fortune.

Small wonder, then, that Gloucester’s subsequent wanderings with his son Edgar (disguised as a beggar and becoming his father’s unidentified protector) evoked such pity and even (after his abortive suicide attempt) an almost sacramental transfiguration into a martyr-like figure, one who had paid a price for his understanding of things and for his short-lived reunitement with the child who truly loved him. His coming-together with the crazed Lear on the heath was a moment of sweetness amid the carnage, a briefly applied balm of shared understanding, here, with the flower-bedecked Lear embracing the blinded and blood-drenched figure of Gloucester, their theatrical duet beautifully voiced by both Henwood and Blackburn, a moment for the ages.

With the other treacherous sister, Goneril, and her husband Albany (Todd Rippon subtly and effectively signalling his ambivalence as a conspirator in the scheme of things, perhaps, like his father-in-law, a man more sinned against, etc….), their dissolution seemed partly wrought by the former’s long-standing marital dissatisfaction. How cruelly and unequivocally Shakespeare characterized this with Goneril’s brief Act 4 tryst with the free-wheeling Edmund, complete with suggestive body-language and hints of impending mutual delight. As for Carmel McGlone’s transported, almost orgasmic delivery of “O, the difference of man and man!”, it ironically brought the house down, the more effectively so for its sudden, highly-modulated expression! By contrast, I thought Todd Rippon nicely judged Albany’s awakening of his own strength of character, both in the face of his wife’s intention to cuckold and usurp him as a husband through Edmund, and in his rediscovery of a sense of loyalty to his king, leading to those words of his bitterly-wrought understanding at the play’s end – “…speak what we feel, not what we ought to say”’.

Director Michael Hurst’s acute observation in his programme note that Lear “goes too far”, beyond what words can say or do, was conveyed in a myriad ways by this production, by its sheer noise, by its stricken silences, by its insensible furies, by its sardonic humour, by its grim desperations and its blazing illuminations and by its unspeakable brutalities set against displays of equally unspeakable love. On stage were both experienced actors playing in a sense their own ripened experiences, cheek-by-jowl with various youthful players fronting up to snippets of ideas and concepts which had the potential to change, modify, augment, enrich their own as yet formative existences – Lear’s doomed yet enduring gesture of union with his daughter Cordelia – “we two alone will sing like birds i’ th’ cage” spoke for this outlandish theatrical amalgam of old and young as beautifully and deeply as any other quality one might think of. For Circa and for the people involved in this production it all seemed to this audience member as beautiful and as deep as one might have a right to receive.

-

May 16th, 2016 at 4:00 pm by David Farrar

With a degree of trepidation I went to see Circa’s performance of King Lear on Saturday night. The trepidation being that since being forced to study Shakespeare at school, I had resisted his work. Also a production that lasts over two and a half hours is normally too long for me.

But I’m glad I did, as it was a stunningly good show. I’d even say it was theatre at its finest. A very fitting way to mar the 400th anniversary of the death of Shakespeare.

The synopsis of the play is:

The story opens in ancient Britain, where the elderly King Lear is deciding to give up his power and divide his realm amongst his three daughters, Cordelia, Regan, and Goneril. Lear’s plan is to give the largest piece of his kingdom to the child who professes to love him the most, certain that his favorite daughter, Cordelia, will win the challenge. Goneril and Regan, corrupt and deceitful, lie to their father with sappy and excessive declarations of affection. Cordelia, however, refuses to engage in Lear’s game, and replies simply that she loves him as a daughter should. Her lackluster retort, despite its sincerity, enrages Lear, and he disowns Cordelia completely.

Ray Henwood as King Lear is masterful – he captures so well a proud wrathful King, and then also his descent into madness. It is hard to imagine anyone else doing the role so well, except perhaps Ian McKellen. Henwood’s eyes are quite captivating as he plays the sad and mad King.

The play is definitely not a comedy, but there are comic moments provided by Gavin Rutherford who is excellent as King Lear’s Fool. His burbling is often cutting and cruel, yet funny.

Other actors who stood out were Nick Dunbar as Oswald, the steward to Goneril (the oldest sister). Dunbar just seems a natural at playing the evil sneering characters.

Ken Blackburn was also an excellent Duke of Gloucester, who tragically allowed one son to turn him against the other.

Also of note was the conflict between the two brothers Edgar and Edmund, portrayed by Andrew Paterson and Guy Langford. Paterson did especially well with Edgar when he pretended to be a madman, to hide from those seeking to kill him.

The play was directed by Michael Hurst, who is an acclaimed Shakespearean director and produced by Carolyn Henwood (who in her spare time is a District Court Judge and chair of the Parole Board!).

The stage design was simple yet effective. Such a large cast (12 principal actors) saw more of the stage used than normal in CircaOne.

An interesting production choice was to have it set in Britain in the 1930s, rather than the ancient past. The costumes were suits, dresses and military uniforms of the era, and it worked. It made the play seem a more modern story, rather than something that could never happen today.

King Lear is a powerful story. It is a tragedy driven by vices of jealousy, lust, power and envy. There is no happy ending, but that doesn’t make it any less satisfying. Of interest, an alternate version of the play was very popular for around 150 years, until 1838. That version had a happy ever after ending for some. But the original Shakespeare version has reigned supreme since then and is regarded as his greatest work for its focus on the nature of kinship and suffering.

The best play I have seen so far in 2016.

Rating: ****1/2

-

King Lear

Taking on the challenge of staging one of Shakespeare’s most notorious pieces, Circa Theatre bring a rendition of King Lear by acclaimed director Michael Hurst to the stage this month.

King Lear follows the story of Lear (Ray Henwood), the King of Britain who decides in his old age to divide his kingdom evenly among his three daughters. When his youngest daughter Cordelia (Neenah Dekkers-Reihana) is asked to prove her love to him, a rift is created and the kingdom is plunged into chaos. As Hurst himself puts it: “you know, lots of sex, lots of violence, and a big fight scene at the end.”

I was instantly enamoured by Ray Henwood as King Lear. He presented himself with conviction, and commanded the audience’s attention. Henwood’s versatility as an actor was reflected in his ability to show a full spectrum of emotion; from love to insanity to loyalty—he projected them all. The entire cast had a visceral synergy, reflecting Hurst’s desire for interesting stage dynamics and patterns.

With no alterations to the Shakespearian prose, Hurst chose to use costume and design to bring this story into a post WWII setting, with lavish fur and silk costumes for the sisters and militant uniforms for Cordelia and the officials. The use of lighting was compelling. Often carrying torches on stage, the actors were able to use shadow play to create huge monstrous figures of themselves on the walls intimidating the audience or even more so, their fellow actors. The set transformed the small space of Circa One into a deceivingly large and empty space. A painting of a faux wooden floor with two high walls intersecting at an angle, and a huge window facing an equally sizeable and menacing portrait of King Lear himself gave depth to the stage.

I attended the show on opening night and was greeted with a friendly and warm atmosphere (and free wine!). Those attending the show were largely of the older generation, but that is to be expected for a show of this density and price range. I could not speak more highly of this skilful and enthralling staging of King Lear, but if you are to catch it, make sure you bring snacks and potentially a blanket—three hours of Shakespeare is quite a commitment.