By Circo Aereo (Fin) and Thomas Monckton (NZ)

In conjunction with Show Pony (NZ)

Directed by Sanna Silvennoinen and Thomas Monckton

Direct from Edinburgh Fringe and the London Mime Festival, last year’s hit returns to Circa!

“It would be no exaggeration to declare Thomas Monckton nothing short of a genius.” – Broadway Baby (UK)

“I doubt very much that you’ll see, in fact I am prepared to bet on it, a funnier show this year…miss him at your peril” – The Dominion Post (NZ)

Fresh from a five-star reviewed season at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and a sell-out season at Circa Two last year, award-winning performer Thomas Monckton returns with his smash hit The Pianist, this time at Circa One!

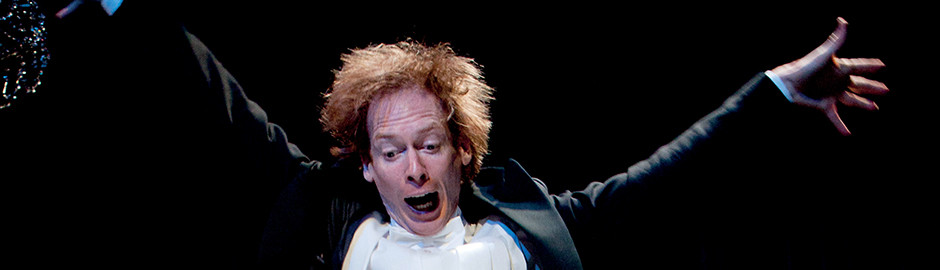

The Pianist is a solo comic contemporary circus piece by Thomas Monckton (NZ) and Circo Aereo (Finland). The show is centered on, in, under, and around the magnificent grand piano. Accompanying this elegant apparatus is the poised pianist himself. Only he is so focused on impressing everyone that before he realises it, his show has transformed from the highbrow concert he hoped for, into a spectacularly amusing catastrophe.

Musical, Physical, Theatre

Performer: Thomas Monkton

Producer: Adrianne Roberts

Assistant Producer: Bonnie Stanway

Finnish Producer: Circo Aereo

In Co-production with: Cirko – Centre for New CircusSound Design by Tuomas Norvio.

Lighting Design by Juho Rahijärvi.

Costume Design by Kati Mantere

Piano Construction: Iain Cooper

Technical Operation: Antony Goodin

NZ Marketing Design: Edward WatsonOPPOSING CHARACTERS IN ONE BODY Reviewed by James McKinnon, 8 Mar 2015

Theatreview already gave Thomas Monckton’s solo farce a five star review when it first ran at Circa in 2014; moreover, after Theatreview described Monckton as “world class” and claimed that The Pianist “could play anywhere in the world,” it did exactly that. Now, on the strength of its genius and its international portfolio of stellar reviews, The Pianist ‘s second run in Wellington is sure to prove popular.

So instead of informing the reader of whether it is a quality show (it is), I will focus on describing what those qualities are. What makes The Pianist, a play without any words and also lacking a conventional plot and characters, so enjoyable to so many people in so many places?

Although there is not a plot in the sense of ‘story’, the action is cleverly and carefully structured. Monckton breaks down the basic action of ‘man plays piano’ to show that this single action is actually a whole series of micro-actions. The pianist enters (attired in tux & tails, he lampoons the high culture image of the concert pianist – and along with it the notion of music as exalted culture). The pianist acknowledges his audience. The pianist prepares his sheet music. And finds his stool… and so on.

Monckton uses physical comedy, corporeal mime and acrobatics to discover and then develop the comic potential of each micro-action. Once he has seemingly exhausted the comic potential of one, something unpredictable happens, propelling us to the next micro-action.

We experience building tension when simple acts, like reaching for a sheet of paper, become increasingly complicated; then astonishment when the trajectory we think we see developing suddenly changes. The simple set – a piano, a chandelier, a curtain – frames Monckton and offers him a few extra opportunities for discovering comic action.

Monckton’s athletic and expressive skills are the engine driving this action. While we have a large repertoire of vague adjectives we use to describe performers as good (“Stunning!”) or bad (“Wooden”), it’s worth going past the clichés and examining what a “stunning” performance really entails (if not a taser).

First, look at Monckton’s balance. Like all of us, he’s always fighting against gravity, but whereas most of us choose to be as stable as possible, Monckton’s body is in precarious balance throughout the performance, which catches and holds the eye. He is always in the process of falling down, and always just catching himself, often only by leaping from one precarious position to another: now he is on one toe; now he is balanced on his hands, on top of a piano; now he is back on his feet – but hanging from them. Even when he stands still briefly, his lanky frame (accentuated by the slim-cut tuxedo) looks like it could fall down at the slightest breeze.

In addition to always being in precarious balance, Monckton always seems to be moving in several directions at once. The opposing tensions in Monckton’s body essentially take the place of the opposing will of different characters in a conventional play. Watch how his limbs, even when he is still, suggest a struggle between opposing forces within the body – even his spiky hair helps sustain this effect. In addition to an acrobat’s flexibility and strength, he has an exceptional ability to isolate individual muscle groups, which he can use to create the impression that one of his legs is trying to walk away from the rest of his body, among other effects.

An acrobat can do all these things, but acrobats do not make us feel anything other than amazement at their technical prowess. What elevates this performance above circus contortionism and makes it theatre is that Monckton directs all these physical skills to an expressive effect. He makes us feel for the hapless pianist. To do this, he makes sure his face and eyes are always as engaged and active as the rest of his body.

The score helps a great deal – The Pianist resembles a silent film in many regards – as does the lighting, but in this aspect as in the rest of the show, Monckton does the heavy lifting.

The Pianist offers much more to discuss about what makes an actor’s performance enjoyable, and since the play is wordless, it is possible to concentrate on these questions without fear of missing any plot-critical information. If you get a chance to see it, you can of course just sit back and enjoy the ride, but for those who are seeing it a second time, or who take particular interest in thinking about what makes live performance work, it is offers a unique opportunity to think about exactly what makes the ride so much fun.

Suitable for all ages.