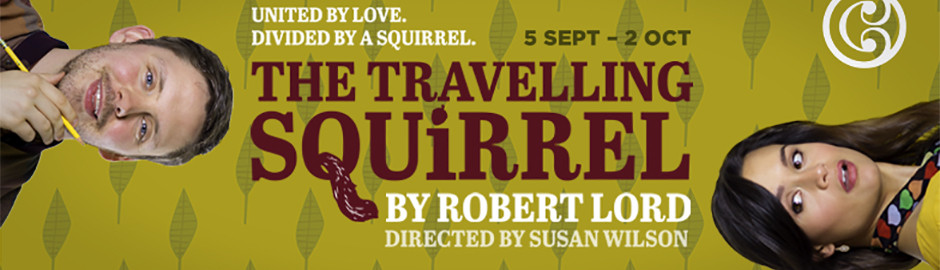

By Robert Lord

Directed by Susan Wilson

NZ Premiere

“We that live to please must please to live” – Dr Samuel Johnson

From Robert Lord, the author of the award-winning and much loved Joyful & Triumphant, comes The Travelling Squirrel, a romp through the fickle nature of the entertainment industry.

Protagonist Bart compares his struggles as a writer to those of Roger the squirrel, a misunderstood painter. Hilarious and packed with larger-than-life characters, this play is a testament to Lord’s ability to write brilliant comedy.

A satire tempered with deep affection, The Travelling Squirrel depicts a dangerous world in which fame and fortune are always temptingly just around the corner

CAST

Bart: PAUL WAGGOTT

Jane: ACUSHLA–TARA SUTTON

Wally: GAVIN RUTHERFORD

Daryl: ERROLL ANDERSON

Julie: CARRIE GREEN

Terry: ANDREW PATERSON

Sarah: CLAIRE WALDRONDESIGN

Set Design and Imagery by JOHN HODGKINS

Lighting Design by MARCUS MCSHANE

Costume Design by SHEILA HORTON

Sound Design: Susan Wilson, Deb McGuire and Andrew DownesPRODUCTION TEAM

Stage Manager: Eric Gardiner

Technical Operator: Deb McGuire

Publicity: Acushla–Tara Sutton

Publicity Intern: Vanessa Immink

Front of House Manager: Suzanne Blackburn

Box Office: Linda Wilson

Set Pack-In Crew: John Hodgkins, Adam Walker, Corrin Gardiner, Jamesina Moffat, Gib Johnston and Davide Aravina

Graphic Design, Publicity & Rehearsal Photography: Tabitha Arthur

Graphic Design Asst.: William Duignan

Production Stills Photographer: Stephen A’CourtREALITY REVEALED THROUGH FANTASY WITH DELECTABLE FLAIR

Reviewed by John Smythe, 6 Sep 2015

It has been said that a sure route to insanity is to work on a fantasy expecting results in reality, yet that is what artists do all the time. Of course once an artefact has been created it can be said to exist but until it is perceived, received and engaged with by others, has it really heppened?

For book writer Bart, in Robert Lord’s The Travelling Squirrel, his untitled prose poem – about a squirrel called Roger and his wife Lucinda in Central Park – is just another pile of paper with black marks on it until someone else reads it, gives it a name and, most importantly, chooses to publish it. Even then, despite its existence in the wider and supposedly more real world, the result in ‘reality’ may not fulfil the artist’s inevitable expectation, be it a fantasy of success, a fear of failure, or both.

For playwrights (and screenwriters), their scripts are blueprints for artefacts yet to be created by teams of artisans, so the expected ‘results in reality’ are even harder to achieve. (Likewise composers, song writers and choreographers.) A poem, short story, novel, painting, sculpture, photograph or graphic design is completed by the artist in its final form, ready to be perceived, received and engaged with. Such works remain accessible and may be returned to with relative ease at an individual’s convenience. Not so a play in live theatre production.

Robert Lord – who wrote about 20 plays in as many years – didn’t live to see the premiere production of his most successful play, Joyful and Triumphant, directed by Susan Wilson at Circa in 1992. He did direct and therefore realise The Travelling Squirrel in its New York world premiere with Primary Stages in 1990. Its first (and hitherto only?) production in New Zealand was at Lyttleton’s Harbour Light Theatre (now demolished, post-quake), directed by Brian Bell more than two years after Lord’s death. Quite why it has taken Circa 25 years to produce it is a mystery.

As a New Zealand playwright ‘living the dream’ in New York, it could be said Robert Lord bit the Big Apple of fantasy to discover the worm of reality that became his muse. As an outsider seeking recognition, his empathy with artists trying to ‘make it’ doubtless made his observations of the infrastructure they sought to infiltrate particularly acute. Multiple strands of reality entwine to create the fantasy that is The Travelling Squirrel. Twist Roger with Bart to get Robert.

Bart is an unknown writer living with a Jane, a high profile TV soap opera star. Over the past five years he has been writing – and had just completed – a prose poem about a squirrel couple in Central Park. Roger is struggling for recognition as an artist (painter) while career-minded Lucinda’s fashion boutiques are so successful she’s thinking opening up other branches. Roger pays his way by working shifts at a Central Park nut stall. Bart pays his way by proof-reading highly commercial works of fantasy (i.e. porn).

The plays follows the incongruent fates of Bart and Jane (echoed in those of Roger and Lucinda). Jane’s star is shining generously as Bart suffers the ignominy of rejection from a writer’s agent who judges his work without even reading it. But the tide turns and Bart is in the ascendant as Jane suffers an ignominy common to many soap stars. Then fortune’s contrapuntal tides ebb and flow once more …

This tidal inevitability is counterpointed by Lord’s insightful character studies, not only of Bart and Jane but also of those who support or impede them: the gossip columnist, the main chancer, the wannabe whatever, the ruthless power broker and the successful artist desperate to maintain her status. Each is flawed and vulnerable in their own ways, employing a range of defence-mechanisms to help them survive.

It is a truism that when plays read well on the page they can struggle to come alive on stage – and vice versa. It takes a specialist skill to perceive the humanity and comedy inherent in the behaviour of Lord’s characters when reading little more than the words they say. It’s ‘where they are coming from’ that makes it insightful and funny. Thank goodness Susan Wilson has that skill plus the ability to cast it ideally, align the designers and crew, and bring it to fruition with just the right tone of heightened reality.

There is more than a touch of Oscar Wilde and Noel Coward (not to mention Bruce Mason’s lesser-known domestic comedies) in the eloquence and sometimes acerbic wit of the characters, as astutely delineated in performance as they are in the writing.

Paul Waggott’s Bart is at his most eloquent when speaking what he has written. His identification with a squirrel has not equipped him well for the entertainment industry jungle. The subtlest of actors, Waggott draws us into his bewilderment, pain and pleasure with consummate skill.

Acushla-Tara Sutton subverts the cliché of the go-getter soap star by making Jane adept at playing the promotional game without being in its thrall. She has great faith in Bart and is in her element using her contacts to help him get the recognition she feels he deserves – but when it all pays off, albeit with some compromising of artistic integrity, it is she who is overshadowed. Sutton’s performance compels out empathy every step of the undulating way.

Jane’s long-standing best friendship with Julie, ever questing for the breakthrough career and relationship, is utterly believable despite – or maybe because of – their very different personalities. Whether Julie is trying to make it as a film producer or creaming it in real estate, Carrie Green insists we do not write her off as a flake by honouring the all-too-human needs that drive her.

Likewise Gavin Rutherford parades the biggest yet most fragile ego in the shape of gossip columnist Wallace White, known to all as Wally – but not to his face unless you want to be snapped at. His infatuation with his latest crush, Darryl, fresh from hearty farming stock, is desperately poignant and somehow makes what could be grotesque engagingly vulnerable.

The enigmatic Darryl engenders intrigue by remaining resolutely silent. Errol Anderson’s attentiveness draws our attention and slowly reveals what Darryl’s game-plan is while garnering laughs and even applause with his posing.

Bluntly honest and something of a social loose cannon, Sarah the talented illustrator is as irritating as she is true in the hands of Claire Waldron. Constantly on the move, she is hard to pin down – which I guess is the point.

Basking in the power that has endowed him with a fake tan, Andrew Paterson manifests Terry the literary agent, not that literature as such has much to do with his value system. Despite his obsession with eye-contact, his ten percent clip of multiple tickets – including merchandising and other promotional deals along with actual author earnings – renders him immune to individual clients’ failures. In short, he’s a sociopath.

While Lord exposes the fickle nature of the arts industries, he captures the exhilaration inherent in the quest for recognition, fame and fortune – and leaves us with the age-old question of whether true love can survive the turmoil and be the healing agent.

Scripted with seamless segues from scene-to-scene, the flow of action carries the story uninterrupted. Marcus McShane’s lighting design and ambient sound (designed by Susan Wilson, Deb McGuire and Andrew Downes) help to indicate relocations of time and place, as do the scene and mood-setting projections on John Hodgkins’ multi-level set.

Sheila Horton’s costume designs are especially eloquent in capturing character, status, values and fortunes as the inexorable tides carry the story.

With delectable flair The Travelling Squirrel uses fantasy to reveal a reality that remains universal. Sure if it was written today cell phones and tablets would pepper that action and change the dynamics but the essential truths are timeless. One may even suggest that social media and ‘reality’ programmes have enhanced a modern audience’s awareness of the world it explores.

This is Circa at its best. Don’t miss it.

“This is surely one of Lord’s funniest plays, just as it is one of the most moving” – Philip Mann

“For two decades, Robert Lord’s plays astonished and entertained theatre audiences with their sharp satire and flamboyant farce.” – David O’Donnell